EXHIBITION REVIEW:

Barbican’s Carrie Mae Weems ‘Reflections for Now’

MAKELLA AMA

EXHIBITION REVIEW:

Barbican’s Carrie Mae Weems ‘Reflections for Now’

MAKELLA AMA

GUIDES US THROUGH ‘REFLECTIONS FOR NOW’

PUBLISHED: 3 SEPTEMBER ‘23

PUBLISHED: 3 SEPTEMBER ‘23

A review of the Barbican’s Carrie Mae Weems ‘Reflections for Now’ - an exploration of the work and career of Carrie Mae Weems in this first major UK exhibition dedicated to one of the most influential American artists working today.

The first thing that greets me when I enter Reflections for Now is the sound of classical music entering my ears. There is a piano softly being played. It rises. It falls. I am alone and with company all at once. I look in front of me and there is a staircase adorned with white bannisters as though the steps that lay in front of me are leading towards an insular heaven. Words in the first room read:

The first thing that greets me when I enter Reflections for Now is the sound of classical music entering my ears. There is a piano softly being played. It rises. It falls. I am alone and with company all at once. I look in front of me and there is a staircase adorned with white bannisters as though the steps that lay in front of me are leading towards an insular heaven. Words in the first room read:

“Even in the midst of great social changes, for the most part our lives remain invisible. Black people are to be turned away from, not turned toward-we bear the mark of Cain. It’s an aesthetic thing; Blackness is an affront to the persistence of whiteness”

I read these words and think about the whiteness of the walls that serve as a backdrop to Weems’ pieces. An interesting extenuation to her words of Blackness being an affront. To the very space we are in and the history it holds perhaps? I think of what it means to be Black and in this space. I think of what it means to bear the mark of Cain (divine protection from premature death) and as I move through each room within this space, I realise how this very mark is one that has enveloped Carrie Mae Weems; an image and film maker // documenter // artist whose work has already left a mark in history after she became the first Black artist to have a retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum (New York), won the prestigious Prix de Roma (2006) and was awarded with a MacArthur Fellowship ‘Genius’ Award (2013). This is already an artist whose legacy will never die.

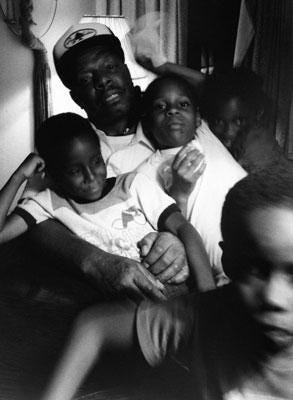

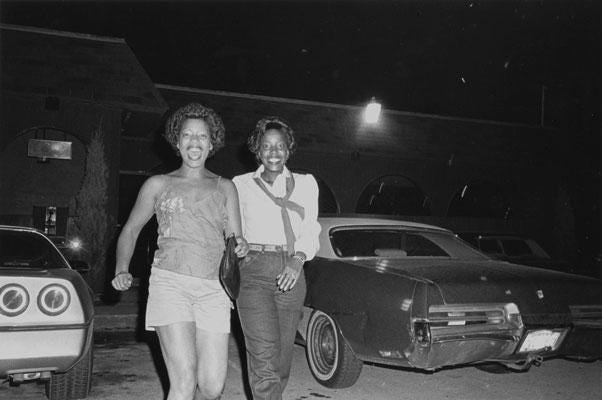

Born in Portland, Oregon (1953) and the second of seven children, Weems’ first love was dance and this was something she initially studied in the 1970s with Anna Halprin (a pioneering choreographer who shaped postmodern dance). Weems started her journey of photography when she was gifted with a camera in her early 20s and began her first project ‘Environmental Profits’ which documented life in Portland. That same year, she also began the series ‘Family Pictures and Stories’, which, over a 5-year period, captured intimate and candid moments with friends and family.

Although the shape of Weems’ documentation has often shifted through different forms, be it dance, photographs or film, one thing that has remained foundational in her practice is her focus on the communities around her and how these interplay with the ever-shifting socio-economic discourses of the world we live in. ‘Reflections for Now’ remains consistent with this theme.

In the second room, the exhibition transports us to 1850 with the series ‘From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried’. I was first introduced to this series at Tate Modern, 5 years prior in 2019. I’d unknowingly walked into a room and was struck by thick, black, large framed prints juxtaposed by a light blue background and following this, vivid oxblood tinges of red. The series consists of 33 images with sandblasted text on glass. Each image is cropped circularly as if to mimic the lens of a camera framing each subject. Watching. Observing. Surveilling. By standing and looking, I realise that I had inadvertently become a spectator much like the photographer who initially took these images; Joseph T. Zealey. A white man who was commissioned by a Harvard scientist to document ‘The Black Subject’ in order to support the theory of polygenism (a doctrine which supported white superiority). Weems acquired these photographs from Harvard Archives and reconstructed them, with text, to breathe life into what otherwise was simply documentation fuelled by racism. Some of this text reads “you became mammie, mama, mother and then, yes, confidant-ha” // ““you became a whisper, a symbol of mighty voyage” // “you became an accomplice” // “anything but what you were ha”. I read these and think about how and whether it’s possible to return agency and humanity to those who have been exploited through documentation and image making, after the fact. By the time I’d made my way round the room, a pool of tears had indeed encroached my eyes as I thought of my grandparents, their own, and theirs before that. From Here I Saw What Happened, and I Cried. Weems has a way of holding and demanding you to bear witness in a way I was not, and still am not quite used to. I was met with this hold, once again, whilst walking through Reflections for Now.

Something I noted throughout the exhibition is the knowledge that a conversation is being had here, between Weems and the watcher (me/you/us). This realisation was emphasised when I reached the third room, whereby Weems shares her background of dance with us through the performance film Holocaust Memorial (2013). During this 2 minute and 49 second performance, Weems asks us to reflect, consider and imagine // contemplate the past // (and) imagine the future. These questions are prompted whilst Weems floats in and out of Peter Eisenmann’s large, greyish-white concrete pillars. These fluid movements are punctuated by short, sharp claps, seemingly bringing us back to life in the eventuality that we become too lost in our own thoughts.

Weems has a way of speaking out of the image/the film/the installation and to the viewer/the watcher/us. At times, it is comforting. In the Kitchen Table (1990) series Weems explores the ability to archive the self, question gender norms and challenge our understanding of relationships all at once. The series includes 20 images and 14 text panels and these were produced whilst Weems was aged 38. We are privy to, at times, blurred photographs (a technique Weems would often use to invite reconsideration of otherwise familiar images). We are privy to tenderly captured moments between man and woman and friends and child. We are privy to prose. Some lines of which I have broken down into a poem and included below:

glistening thinking

crystal light of august/

september sky

so tell me baby

What do you know about this great big world of ours?

several wrong turns

with conviction

teach me?

mood for love

ole black magic

hand in

hand

twinkle of august/september sky

lucky stars

fingers crossed

lucky stars

fingers crossed

In other moments, Weem's ability to hold conversation with the watcher (me/you/us) is utterly devastating, as felt in one of the final rooms of the exhibition which features a diorama (akin to a vigil) through which Weems accentuates the link between the long history of trauma caused by colonialism and contemporary oppression. In this, ‘It’s Over – A Diorama’ (2021), Weems presents a tribute to Black people who have lost their lives due to police brutality in the US. On display, we see candles. We see balloons. We see flowers and stuffed animals- objects all referencing the many memorials created by families and communities affected by ongoing state sanctioned violence. Admittedly, my time in this room was short. As I entered, I was met by a white staff member of the Barbican who was sitting at the Diorama, simply looking-at-me – looking-at-the-vigil. The realisation that the process of spectatorship would never really die, dawned on me, and between tears I hurriedly walked on determined not to allow myself to break down in front of whiteness. I understood that the staff members’ presence in this room was not their fault. They were working. They had a job that they were simply doing. Nonetheless, it made me query what institutions like the Barbican were doing to prevent the very process of racially undertoned spectatorship from continuing. Could they not have hired someone who was non-white to invigilate that room? Did a member of staff need to be present at all? What kind of additional support would have been provided, regardless of race, to whoever would have been sitting in that room, enveloped by memories of death for countless hours whilst on shift? I have not returned to that room since. I hope that upon my return (the overall hold that I felt means I have no choice, but to return), my experience in that room at least, will not be the same.

In Reflections for Now, much like in the everyday synchronicities of life, everything is overlapping, everything is connected. We are invited/demanded/coaxed to think introspectively. I leave and I ask myself a question Carrie Mae Weems herself had posed at a talk earlier in the month, at the Barbican: “what is the purpose of museums?”. I get home and I ask my friends about the last time they felt seen at a gallery/ what did this feel like? / In what state, did they leave? I wake up and I cry.

Click here to book.

In Reflections for Now, much like in the everyday synchronicities of life, everything is overlapping, everything is connected. We are invited/demanded/coaxed to think introspectively. I leave and I ask myself a question Carrie Mae Weems herself had posed at a talk earlier in the month, at the Barbican: “what is the purpose of museums?”. I get home and I ask my friends about the last time they felt seen at a gallery/ what did this feel like? / In what state, did they leave? I wake up and I cry.

Click here to book.